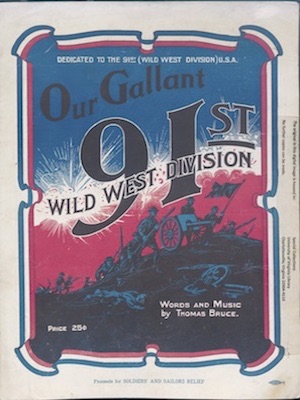

Our Gallant 91st Wild West Division

Live Version

Studio Version

Sheet Music

Student Essay

World War I Sheet Music, the German “Hun,” and the Shaping of American Cultural Identity

By the time the United States entered the First World War in 1917, and despite President Woodrow Wilson’s official policy of neutrality at the beginning of hostilities in 1914, the mechanisms by which the American public could be influenced through heightened use of propaganda on the part of the government – specifically the Committee on Public Information – had already been set. The use of propaganda to shape public opinion was not a phenomenon unique to World War I, as it had also played a role in most past U.S. wars. Though not government-sanctioned, the best known example of this is perhaps William Randolph Hearst’s use of “yellow journalism” during the Spanish-American War at the turn of the century. Exaggerated stories of Spanish atrocities – which, in the case of the USS Maine, were coupled with falsehoods – sparked outrage. This can be directly compared to both England and Germany’s attempt to tip America’s “neutrality” in their favor after 1914. England deployed a method similar to Hearst’s when describing alleged German atrocities, and thus succeeded in spreading its narrative. Therefore, it is not surprising that the CPI continued to build upon these methods and exploit any established fears to an unprecedented level under the guise of maintaining national unity, patriotic sentiment, and domestic support for the war. The CPI commonly employed the term “Hun” to characterize the German enemy as a “barbaric” and “primitive” threat to the safety of the American public.

“Let all who fall into your hands be at your mercy. Just as the Huns a thousand years ago, under the leadership of Attila, gained a reputation in virtue of which they still live in historical tradition, so may the name of Germany become known.” – Kaiser Wilhelm II, July 27, 1900.

While the Kaiser meant to celebrate the prowess of the German military and the German people when he addressed soldiers departing for China to crush the Boxer Rebellion, the international community saw the momentous occasion rather differently. As tensions continued to mount in Europe across the next decade, the future Entente powers co-opted his use of the term “Hun” and flipped it on him and his nation. Rather than a positive, progressive power, the Germans were instead akin to the fifth century nomads who sacked part of Europe, leaving villages pillaged and burned in their wake; if the Germans were not stopped, contemporary Europe would meet a similar fate. Even if only understood in its very general historical context, this connection inspired fear. It effectively painted the Germans as an enemy, and was therefore used as a propaganda tool to mobilize public opinion and troops against Germany – both in Europe and, because of the constant flow of information across the Atlantic, the United States.

“Hun” was widespread across all forms of propaganda. Though assertive, eye-catching posters were commissioned by the government, printed by the thousands and plastered in most public spaces, they had for the most part one purpose: to encourage Americans to purchase Liberty Bonds in order to “beat back the Hun”. A much better illustration of the term’s scope comes with a brief examination of sheet music produced during the war.

In “Go Get a Hun” by Arthur Angel Machet, for example, a grandfather encourages his grandson to follow in his footsteps and go to war to bring his family honor and make them proud.

Go get a Hun son, go get a Hun before a Hun gets you,

And just keep him on the run, with your great big Yankee gun (gun)

And we’ll all be proud of you.

“Please Don’t Call Me ‘Hun’” by W. R. Wight employs a clever pun – that would not have existed without the extensive use of “Hun” – in a romantic song about a woman watching her lover and his regiment leave for Europe.

Call me honey call me darling, call me either one,

Call me any old pet name, but please don’t call me “Hun”

For that name has lost its sweetness

On land, or air, or sea,

So please don’t use that name, my dear, when you’re addressing me.

Both of these songs operate within the context of a young man going to war, but through the lens of family or intimate relationship. The first might encourage enlistment, and the second address home front attitudes towards Germans, but both use “Hun” to deliver strong messages about societal expectations during war.

The prevalent use of the term “Hun” and the way it was depicted in propaganda material during World War I reflected deep racial anxieties held by the Allied powers with regard to their own societies. Nicoletta F. Gullace, in her article titled “Barbaric Anti-Modernism: Representations of the “Hun” in Britain, North America, Australia, and Beyond,” is one of the few scholars to argue that these anxieties were exploited on a global scale to further anti-German sentiment and to define the true purpose of the war: the protection of Western European culture and civilization against the “anti-modern” and therefore “primitive” insurrections of the enemy. The idea of the “primitive” came not only from the understanding of the Asiatic Huns as a people of destruction and brutality – and, as Gullace points out, the Huns’ historical lack of regard for cultural monuments and learning seemed parallel to the Germans’ contemporary destruction of many symbolic sites in Europe – but also following a long tradition of perceiving Africans or those of African descent as “uncivilized” or “savage.” In what Gullace dubs a “racial redefinition of Germany,” Allied propaganda applied ethnic tropes associated with both groups to turn Germany into a “primitive,” “savage” society. Most significantly, in the eyes of the Allies, this practice helped justify going to war.

Related Resources

Aubitz, Shawn, and Gail F. Stern. “Ethnic Images in World War I Posters.” The Journal of American Culture 9, no. 4 (Winter 1986): 83-98.

Bruce, Thomas. "Our Gallant 91st Wild West Division." United States: Thomas Bruce, 1919.

Bryan, Alfred, Edgar Leslie, and Maurice Abrahams. Big Chief Killahun. New York: Waterson, Berlin & Snyder Co., 1918.

Crawford, Richard. “After the Ball: The Rise of Tin Pan Alley.” In America’s Musical Life, 471-493. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

Finson, Jon W. “The Romantic Savage: American Indians in the Parlor.” In The Voices That Are Gone: Themes in 19th-Century American Popular Song, 240-269. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Gullace, Nicoletta F. “Barbaric Anti-Modernism: Representations of the “Hun” in Britain, North America, Australia, and Beyond.” In Picture This: World War I Posters and Visual Culture, edited by Pearl James, 61-78. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

Hart, Al. "Ah Didn’t Raise Mah Boy to Be a Slacker." Omaha: The Hospe Music Co., 1917. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014561747/.

Kingsbury, Celia M.. “The Hun Is at the Gate: Protecting Innocents.” In For Home and Country: World War I Propaganda on the Home Front, 218-261. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010.

Machet, Arthur Angel. "Go Get a Hun." 1911. Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/2009371133/.

Mortimer, G.A., and William R. Wight. "Please Don’t Call Me 'Hun'." 1918. Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/2013567889/.

Ross, Stewart Halsey. Propaganda for War: How the United States Was Conditioned to Fight the Great War of 1914-1918. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 1996.

Saffle, Michael, and Robert Groves. “A Break in the Color Barrier: African Americans and World War I Sheet Music.” American Music Society Bulletin (Winter 2017). https://search.proquest.com/docview/1944540123?accountid=14541.

Sawhill, Franklin Clark, and Kathryn I. White. "Heep Plenty Hun Scalps." Cincinnati: The Willis Music Company, 1918.

Strothmann, F., Artist. Beat back the hun with liberty bonds / F. Strothmann. United States, 1918. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/94505100/.

Written by

Tess Irelan is a senior at the University of Virginia, double-majoring in music and history, and minoring in German. During the spring semester of 2017 she studied abroad in Vienna, Austria, where all three areas of study intersected and sparked an interest in the World War I-era. With this framework in place, Tess was excited to shift her focus to sheet music produced in the United States and what it reveals about American wartime society.

Song Information

Recording Information

Performers

Crystal Golden, Soprano, is a Master's student in Vocal Performance at George Mason University. She won First-Place at several state and regional competitions, and has performed major operatic roles both at GMU and internationally (Amalfi, Italy). She has received numerous awards in academic achievement, has studied abroad at the University of Oxford, and is a member of both Phi Kappa Phi and Phi Beta Kappa.

Estrella Hong is currently a doctoral student in piano performance at George Mason University in the studio of Dr. Linda Monson. She is also a graduate teaching assistant in keyboard skills. She studied piano at the National Conservatory in Buenos Aires, Argentina, as a young pianist. Additionally, she graduated with a Biochemistry degree at UCLA and assisted various research projects in Whitesides lab at Harvard University.

Live Version

Eli Stine is a composer, programmer, and educator. He is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Composition and Computer Technologies as a Jefferson Fellow at the University of Virginia. Stine's work explores electroacoustic sound, multimedia technologies (often custom-built software, video projection, and multi-channel speaker systems), and collaboration between disciplines (artistic and otherwise).

Studio Version

Song Transcription

[Verse 1]

Our Western boys are home again

with victors battle song

With happy smile and martial stride,

They thrill the cheering throng.

Their task is done, they beat the Hun

Of all the world accurst

“Our hearts we give may long you live

Our Gallant Ninety First!

[Chorus]

They’re home from France, they’re home from France

Our boys who know no fear

“Welcome, each and ev’ry one

Let’s give a rousing cheer (Whoopee!)

Hooray then boys, hooray, hooray

You fought without dismay

And now you’re home from o’er the foam

The Wild West won the day.

[Verse 2]

Our Western boys are brave and true

At home or o’er the sea

They kept the old red white and blue

The emblem of the free,

And now they’re home,

let’s make them glad they sent the Hun accurst

Across the Rhine in double time,

Our Gallant Ninety First!

[Chorus]