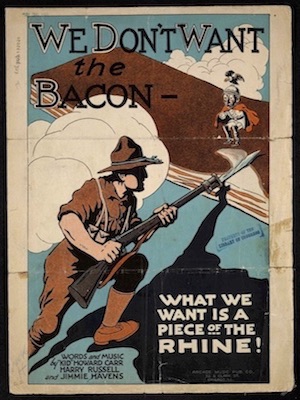

We Don’t Want the Bacon, What We Want is a Piece of the Rhine

Live Version

Studio Version

Sheet Music

Student Essay

We Don’t Want the Bacon

“We Don’t Want The Bacon, What We Want is a Piece of the Rhine” by Howard Carr, Harry Russell, and Jimmy Havens is a comedic song that was published in Chicago at the conclusion of World War I in 1918. In addition to being issued as sheet music with this visually stunning cover, it was recorded on Victor Records the same year by the Peerless Quartet who were one of the most commercially successful vocal groups at the time.

“We Don’t Want The Bacon” recalls a soldier’s prior obligations and declares his new intentions. As men shipped out to expand the war efforts against the Huns realizing that they were no longer contributing to family earnings, but what would be an earning for America as a powerful nation of defense. People far and wide could joyously and chorally exclaim the desire to defeat Germany and change the occupancy along the Rhine River. From beginning to end, this song showcases a confidence withholding any fear that the soldiers may be feeling for a determination that the Great War will be won by defeating German opponents.

This music paints a picture of American glory, while comical and catchy, that children could and would easily sing. Using the commercially successful vocal groups, educational theorists could shape curriculum to define ideal Americana, exuding a confidence and sense of patriotism that would be carried through the ages. In many ways, World War I shaped how violence is presented and perceived as seen through the educational lens. I would argue that it desensitized children to war due to the child-centered war propaganda available at the time.

At the turn of the century, there is a shift in art, music, and culture in addition to a new educational foundation whose characteristics we continue to see in public schools today. While art and music began to shift away from classical standards, schooling began develop rigid structuring. Prior to the 20th century, there was little to no uniformity nor regulations for the public-school system in America with the exception of Horace Mann’s Common Schooling beginning in New England. Mann was an advocate for structured learning for students in a general area through which principles could be established for the common good (Mann and Cremin, 1957). The curriculum focused on reading, writing, arithmetic, and other subjects, but also included teachings related to Protestant beliefs. However, Mann received push back due to the lack of religious freedom of an ever-growing diverse America even though one of the sole purposes was to instill good morals and obedience in students (Mann and Cremin 1957, 15). Mann’s reign is believed by many scholars to have concluded by the turn of the century. Even so, the idea of using schooling to further develop an upstanding citizen with an underlying theme of pushing one’s own principles onto youth continues to be a trend.

As we move into the 1900s, more regulations were put into place enforcing students to attend public schools through the primary level. While not all states were mandating this, two-thirds were, many of whom provided secondary education for students as well. It is also here that we begin to see a trend of progressive education coined by theorist John Dewey. He also encouraged philosophical ideas with Christian undertones, but unlike Mann’s Common School, Dewey’s ideas seemed so radical at the time because they were not the traditional one-room school method of teaching. Dewey believed in an experiential school in which the students would take charge of their own learning through experience and process as well as more of a pragmatic approach to individuals and their participation in democracy. In the short video clip cited below with Dr. Hicks, he explains that one of Dewey’s ideas is the longevity of a democratic society based on individuals that participate accordingly (Hicks, 2010).

While Mann’s and Dewey’s structures of learning are radically different, they sought to have the same outcome – a more informed upstanding citizen to participate in democracy through good moral fiber. This trend in education is not solely sought after by educational theorists but by the American government once America finally enters World War I, even to Woodrow Wilson’s dismay. An extremely well-known idea of recruiting people through use of a sense of commonality seen in war propaganda and sheet music is not limited to the adult population who can serve their country by fighting here on the home front and overseas. War propaganda was quickly adapted to both help and exploit children, and to almost desensitize Americans to war.

One of the themes that was so often used was an educational approach to appeal to mass audiences to garnish support for the men fighting through literature and song. It trickles down to children through use of wartime games and alphabet books (Watkins, 2003). The alphabet books could introduce children to vocabulary centered on war that would not be relevant to them otherwise. Through use of these materials, educators and families could teach children about war in an honorable way that excludes negativity often associated with war. At the same time, they would be shaping students to acknowledge the impact of war that places America as a defensive powerhouse.

Yet another tactic used during the Great War was educating through use of song and sheet music. Instead of learning about values and a strictly adhered to moral path in a typical religious service manner, students would learn the American story through the songs that appropriated war in the school system. Since sheet music was made so readily available to women by the many composers of Tin Pan Alley in New York City, it only made sense that children would also be a target of such marketing. Tin Pan Alley was a hub of sheet music production in the early 20th century that was constantly turning out music for listening pleasure across America (Crawford, 2001). In part, this music would facilitate discussions on war-related topics such as the enemy, war bonds, the service men and women, and the greater effects on the home front. However, often you would find that song would stay far away from the violence that ensued, only sometimes veering close to that boundary and in a comical way, such as in “We Don’t Want the Bacon.”

Related Resources

Crawford, Richard. “After the Ball: The Rise of Tin Pan Alley.” In America’s Musical Life: A History, 471-493. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

Dewey, John, Philosophy and Civilization. New York: Minton, Balch and Company, 1931.

Havens, Jimmie, Harry Russell, and Howard Carr. "We don't want the bacon what we want is a piece of the Rhine." Chicago: Arcade Music Pub. Co., 1918. https://www.loc.gov/item/2013564681/.

Hicks, Stephen, PhD. "John Dewey on Education, Part 1." YouTube (video blog), July 21, 2010. Accessed May 2, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M_dhS83XRyQ.

Mann, Horace, and Lawrence Arthur Cremin. The Republic and the School: Horace Mann on the Education of Free Men. New York: Teachers College Press, 1957.

Watkins, Glenn. “War and the Children.” In Proof through the Night: Music and the Great War, 103-122. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003).

Written by

Samantha Thomas is a graduate student in the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia and is currently working on her Master's degree in Elementary Education. She is thankful for the opportunity to work on the ReSounding the Archives project this spring.

Song Information

Recording Information

Performers

James Stevens is a second-year graduate student pursuing a degree in Vocal Performance in the studio of Professor John Aler at George Mason University. His recent Mason Opera appearances include Albert Herring in Benjamin Britten's Albert Herring, Lord Tolloler in Gilbert and Sullivan's Iolanthe, and King Kaspar in Menotti's Amahl and the Night Visitors. His recent concert appearances include singing with the Central Maryland Chorale and the Symphonette at Landon.

Faith Ellen Lam is a sophomore Honors College student at George Mason University where she is a dual major in Music Performance and English. She is in the piano studio of Dr. Linda Monson. She has performed in such prestigious halls as Weill Recital Hall in Carnegie Hall, New York, and the Millennium Stage at the Kennedy Center, and has been invited to play in numerous masterclasses with artists such as Stanislav Khristenko, Jeffrey Siegel, and the Ensemble da Camera of Washington.

Live Version

Eli Stine is a composer, programmer, and educator. He is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Composition and Computer Technologies as a Jefferson Fellow at the University of Virginia. Stine's work explores electroacoustic sound, multimedia technologies (often custom-built software, video projection, and multi-channel speaker systems), and collaboration between disciplines (artistic and otherwise).

Studio Version

Song Transcription

[Verse 1]

If you read our history, why it will show

That we have always held our own with any kind of foe

We’ve always bro’t the bacon home, no matter what they done.

But we don’t want the bacon now, we’re out to get the Hun.

We…

[Chorus x2]

… don’t want the bacon, we don’t want the bacon,

What we want is a piece of the Rhine.

We’ll feed “Bill the Kaiser” with our Allied appetizer,

We’ll have a wonderful time.

Old Wilhelm Der Gross will shout,

“Vas is Los?”

The Hindenburg line will sure look like a dime;

We don’t want the bacon, we don’t want the bacon,

What we want is a piece of the Rhine.

[Verse 2]

When this trouble started they said we did not have a chance,

They could not figure out how we could get our men to France

But we defied the U-Boats, for out motto is to win

We’ve got them into France right now, they’re headed for Berlin.

[Chorus]

We don’t want the bacon, we don’t want the bacon,

What we want is a piece of the Rhine.

We’ll crown “Bill the Kaiser” with a bottle of Budweiser,

We’ll have a wonderful time.

We’ll defeat the subm’rine their Hindenburg machine;

There won’t be any flop when we go over the top;

We don’t want the bacon, we don’t want the bacon

We want a piece of the Rhine.